The Penguin VFX Are All About 'Making You Feel It'

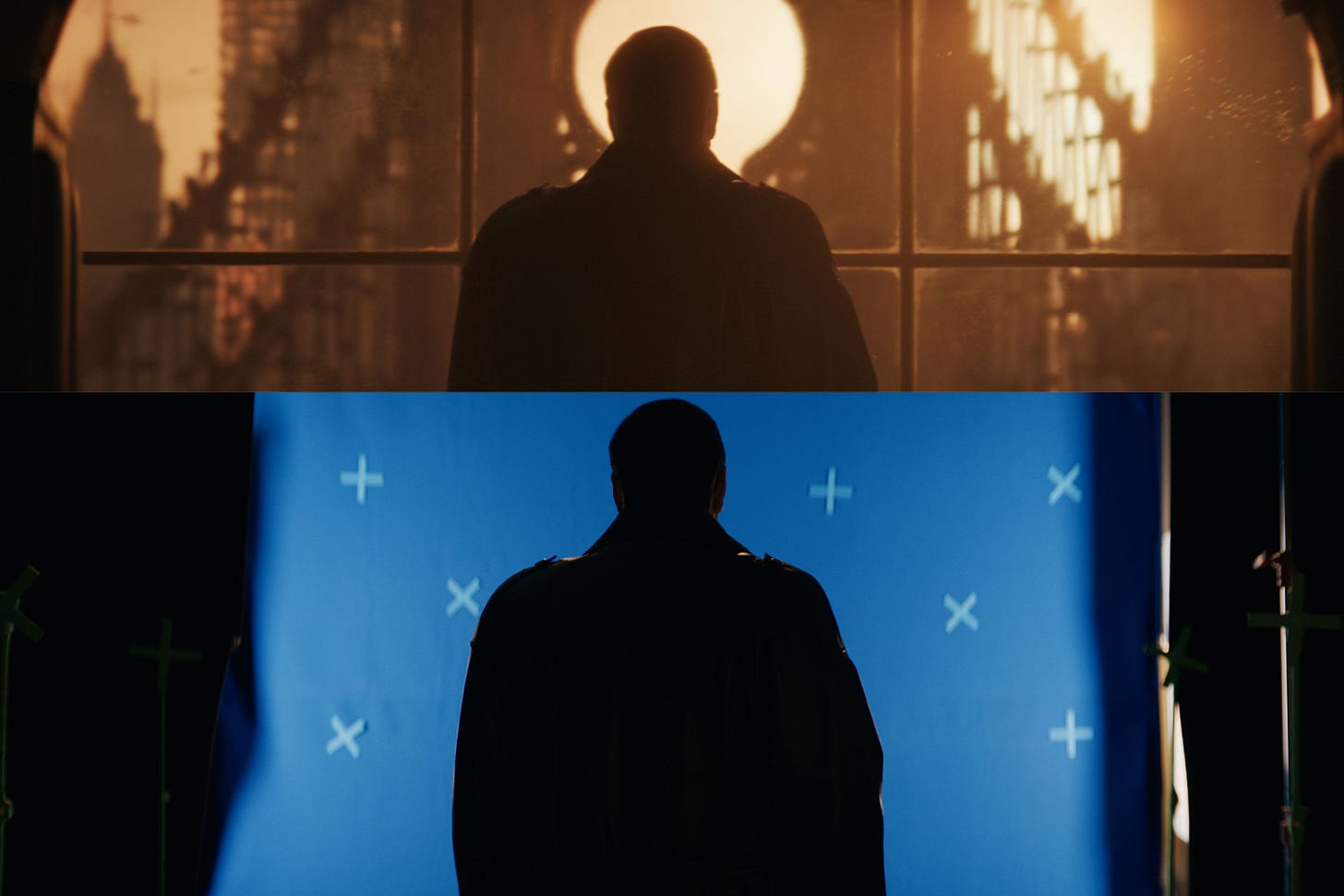

VFX supervisor Johnny Han, on-set supervisor Alexandre Prod'homme, and Accenture's Emanuel Fuchs talk about bringing Gotham to rain-soaked life.

Welcome to the wild and wonderful era of Emmy Awards: Phase 1, when the arbitrary rules governing what is timely are set aside, and we can discuss projects that were released weeks or months earlier and deserve to be top of mind again. The Penguin premiered on HBO September 19, 2024.

Visually, The Penguin is one of the most rewarding watches in recent memory. Not only does the HBO series—a direct sequel to Matt Reeves’ 2022 The Batman—boast a cinematic sweep, but there’s also Colin Farrell’s transformation into Oswald Cobblepot, aka The Penguin, a sumptuous production design by Kalina Ivanov, and Cristin Milioti’s can’t-take-your-eyes-off-her performance as Sofia Falcone, an agent of fiery chaos. And supporting all of it are the VFX from Johnny Han and his team, which range from a rolling wave that destroys much of Gotham in Episode 3 to creating the rainy, noirish streets that Oz hopes to control.

That rain came courtesy of a lot of VFX work when filming in winter made it impossible to get the right permits to wet down the streets of NYC. Han spoke about his work on the series, alongside on-set supervisor Alexandre Prod’homme and Emanuel Fuchs, a VFX supervisor at Accenture Song, who oversaw multiple matte paintings and establishing shots of Gotham—and the final shot of the entire season.

How do you begin work on a project like this, which will rely so much on the visual style of The Batman? What conversations were you having?

Johnny Han: We knew from the beginning that our story takes place two weeks after the events of the movie. So it didn't just have to feel the same, it had to really feel like a handoff. That was very important to [showrunner] Lauren LeFranc and Matt Reeves. And we knew we had to not only match it on a relatively meek television budget, but also bring our contribution.

And a large part of that was exploring neighborhoods that may have been mentioned in the film, but they were never seen. In those cases, we had a little bit more room to be inventive, pushing the boundaries of what the tone was for the show. We did a lot of daytime Gotham. We did a lot of underground. And we also got to see what the suburbs looked like, which is where the Falcone mansion was.

And on the visual effects side, Dan Lemmon, who visual effects supervised a film, we had a great call where we went through the whole film scene by scene and every visual effects shot to say, “Oh, by the way, Matt really liked this,” or, “Hey, in this place it doesn't look like we did anything, but Matt was very specific to add a building here or that the water had to flow here.” And that was tremendously helpful. Often, you never hear from the guys who did the last one. But there was such goodwill and a good friendship because everyone just wanted it to be as good as it could be.

Alexandre Prod'homme: Early on, there was discussion about using the same lenses [as The Batman]. And even for HBO, it was the first time that they were pushing to have not a true 16 by 9, but we were going a little bit wider. So we preserve a lot of the characteristics of the original lenses used on the films.

Those lenses and the rainy, wet streets were such huge parts of The Batman.

Emanuel Fuchs: There’s a lot of water drops hitting lenses, right? So this is a visual style that Johnny wanted us to explore early on. For that reason, Johnny and his team shot a library with a lot of these wet flares, we called it. So that was basically taking glass elements in front of the camera, smearing all different sorts of gels on there, and then with the lighter torchlight, lighting into the lens. And then getting these nice organic layers and elements, and that's something we then recreated in CG, putting them in our shots whenever possible.

Johnny Han: [During] principal photography, we didn't have that kind of direct aberrations on the glass. So we shot these elements on black so that, in post, we could dress up shots that looked maybe too perfect to help bind the image together.

And Alexandre, what was it like on set?

Alexandre Prod'homme: Honestly, it's mostly paying attention that we shoot it in a way that's not too disruptive for a budget, because there is this key moment where we know we want to spend the money on screen for bespoke VFX, but also sometimes you need to accommodate the shoot. You're almost a consultant when they have an idea, you're here to help them fulfill their vision without compromising. But the day-to-day is to stay with the directors and the DP, but also gathering references, making sure we have all kinds of toys in our department to support people on the vendor side. Like Accenture, we need to make sure that at the end of the shoot, we have a package that can go to them and help them do the actual VFX work. Also, on our show, we were pioneering new technologies.

Johnny came up with the idea of interactive light for muzzle flashes on guns because our show did not use real guns. We had solid plugs, but we also had a contraption, which, every time you trigger it, will create a very bright LED-type of light. In post, it always feels a bit fake when you add light and there was nothing on the day. So we were here to push for as much interactive light as possible. Johnny can talk more about it.

Johnny Han: That’s a good example of how visual effects isn't always post-production and computer graphics. A lot of times, our job on set is to help prevent overuse of visual effects by seeing if there are solutions on set that will help alleviate what we have to do in post. The flash guns were a multi-headed beast between props, lighting, visual effects, and stunts because everyone had to be involved. But it was a way that we could shoot it that would make the visual effects look much more real. Some shots we didn't need to do any more because these flashes, if you had a close-up shot of someone, but someone else in the room was shooting, you get the flash of light on their face, and a bit of the reaction from the actors. If you were just doing a close-up, usually they'd just have someone off-camera say bang, and then the actor has to react to it. But with the light, it gave everyone something to play to. It may not seem like visual effects because it's not something being done in post, but it is us who raise our hands and say, “Hey, can we try to do it this way?”

And then that scored a VES nomination for emerging technology! And I imagine being second unit AD fed your VFX work, and vice versa.

Johnny Han: Often on a show like this, there are tons of visual effects elements to shoot. Especially if we go photographic heavy, it could mean shooting blood splattering onto a mannequin's head. It could be this wall of wood debris that needs to get knocked down, but it's not safe to do on set, so we'll shoot it against green screen. And as this stuff snowballs, it becomes evident that we need a whole day to shoot this in production. It's interesting how it falls into visual effects; it wouldn't seem like the first thought, but if you think about what other person is there from beginning to end, the visual effects supervisor is often one of the first hires in prep because we're helping visualize a show all the way to final color. We are a good brain trust of knowing what every script is about, what every story point is, we've been in the edit bay, we've seen the problems in the edit. We're like, they're missing a shot here. So in this case, as second unit director, I get to shoot those little bits of drama and insert scenes that the director's too busy to do, but I also get to tick off our needs for visual effects.

What an amazing way to be proactive about what editors might need.

Johnny Han: And sometimes it can be a whisper or a text from edit: “Hey, do you think there's anything we can do about this?” One of them was the door to the secret tunnel entrance that Oz and Victor break into in the middle of the night. It just didn't look so secret. So how can we make this feel more secret or at least more discreet? And we said, “All right, let's film a bunch of plywood planks as if they had boarded up the door on green screen.” And we had a rig to make it collapse. That's what's in the show. We had to make it more clear that no one else would've stumbled across this place. HBO is very serious about all things lead to story and all things lead to character. We never do these things just for fun. It really is an effort to tighten every bit of the story.

Do you each have a favorite shot or sequence?

Emanuel Fuchs: I'd say the opening shot, where we boom all the way down to the lowest level in the city, and then the Maserati coming in. That was quite a fun shot to work on. So many little details—all the rain, the flares, the puddles where we reflect things—that we needed to create digitally.

Alexandre Prod'homme: It is not exactly a shot, but more like a moment. It's just after he threatened the council member [with pliers in his nose], and then he just helps him reverse his vehicle and leave. It says a lot about the character of the Penguin.

Johnny Han: I'll just say one more thing about that scene. Originally, it was written not as pliers on the nose. I think it was [Oz] burning his stomach with a crème brulee torch or something. But it ended up being a practicality issue of the prosthetic of the stomach and some logistical issues. And so the writers came up with him using pliers. And I think in the end it's such a good example of how the constraints make things better. Oz isn't a wealthy person yet. That's something he could have had in his toolbox of stuff. The torch thing is a little specific, and I think pliers and the tactileness and the way the actors played off it, it's just a good moment.

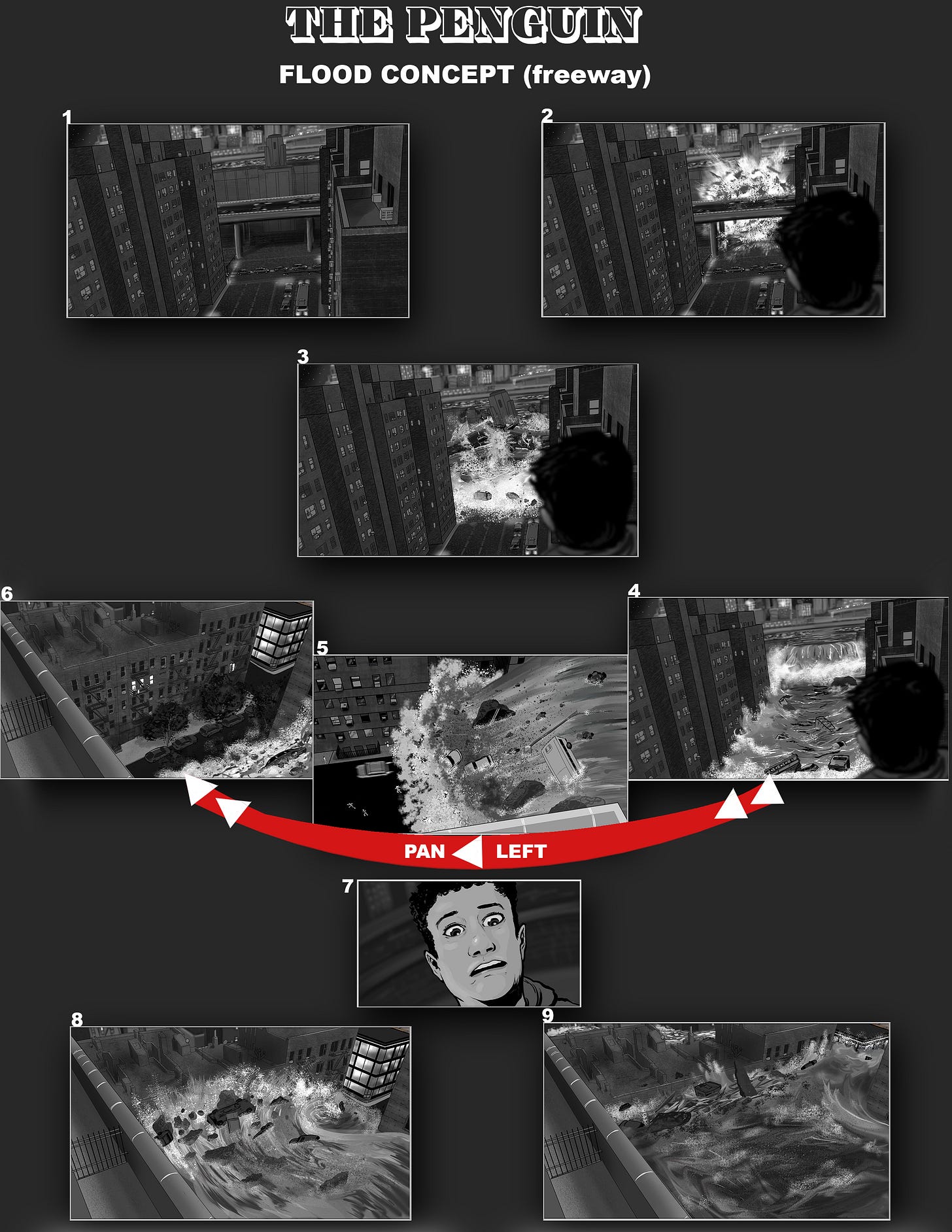

I think my favorite moment was the flood in Episode 3, where Victor witnesses the same events from the movie but from his perspective. It was so powerful because a big flood is usually construed in the visual effects world as a spectacle event, the bigger the better, and the more stuff you throw into it, the cooler. But we really had to shake that off and hone in on the narrative the story set up, to anchor Victor's point of view for the whole series, his origins of how he lost his whole family and everything he had right before his eyes. Taking something that is usually this big, flashy spectacle event, but making it this emotional, visceral, and tragic experience that we're roping the viewers into is unexpected. When you see that scene, you're not expecting this huge emotional gut punch in the first act of the episode.

It's a real testament to everyone involved in how it was photographed, how Rhenzy [Feliz] played it, the visual effects work, and the simulation work; Goran Pavles was a VFX supervisor for the water shots. To take something that's normally so big and bombastic, but instead make it this very eerie and silent and emotional moment, I think is the success we're always trying to go for in VFX, where it's about making you feel it and not see it. Obviously we're seeing it, but it means nothing if you're not feeling it as well.

The Penguin VFX team scored three VES nominations, winning two. They submitted Episode 3, “Bliss,” for Emmy Award consideration. All three are in agreement: the go-to at craft services is coffee. “And gingert shots,” Prod’homme adds.